By Walter C. Hornaday

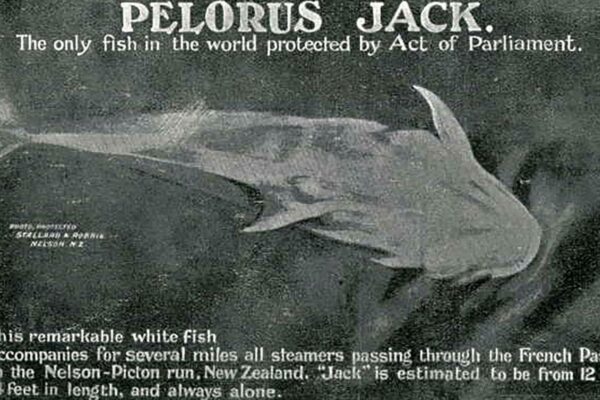

The following article by Walter C. Hornaday, appeared in the Sunday Star, Washington D.C., July 5, 1914. It gives a detailed account of the famous life of Pelorus Jack also known as Kaikai-a-waro, a Risso dolphin from New Zealand.

The native Maori tribe of Ngati-Kula, New Zealand honored and sang to “Pelorus Jack” an albino Risso’s whale. In 1911, Kipa Hemi, an old historian for the Maori shared the story of how this small toothed whale served his family for at least 275 years.

This fish has for many generations past been the atua or sea god of my family. My ancestors were piloted on their canoe voyages by Kaikai-a-waro and some were even saved by him. He is no common creature of the ocean.

You must know that in ancient times every Maori chief had his particular family atua, or god, besides the national gods of our race. Some of these family and personal atua were in the form of birds, some were in the form of fish, some were stones. I am descended from Kupe, the great navigator who crossed the Moana-nui-a-Kiwi (the Pacific ocean) in his canoe Matahourus, who was the first as far as history goes to explore the shores. Kupe’s descendants lived on the northern shore of Cook straight until about 11 generations ago, when one of them, the chief, Matuashas-tere, crossed to the South Island and the islands of the sounds; and with him, escorting his canoe, came my godfish “Kaikai-a-waro” or Pelorus Jack” as you call him.

When my forefather, Matuahautera crossed the sea of Raukawa to the Wai-pounama, there came along with him this god fish and that was the first time he was seen in the waters. The canoe crew paddled along and Kaikai-a-waro came rolling along with them, shooting away sometimes ahead and sometimes abreast of the canoe bows. The crew paddled gayly along and chanted their canoe songs, for they were cheered by the sight of their friendly pilot. So, they crossed the straight and entered the sound of Holere and there “Kaikai-a-waro performed some strange feats. They are wonderful things, but they are true, for was he not a god?

Swimming along in advance of Maturahautere’s canoe, Kaikai-o-ware led the way up the winding Sound of Holere, expecting to find a clear sea passage through between the hills to the other side. He went until he arrived at the very head of the sound, near where Havelock Town now stands. One of the spots in the lower part of the channel is where the Pelorus River flows into the sound. On his way to the mouth of the sound was a little island in the bay. There is a rock there, between the island and the eastern mainland, off Tawa Bay and on the mainland opposite is the cave of a dragon or sea god.

In ancient times, Maoris were very cautious when they went out fishing near that rock. Should they try to pass without observing the necessary ceremonies, the taniwha living in the cave would become angry and, in his wrath, would capsize the fisherman’s canoe.

Well, Kaikai-a-waro returned to the mouth of Holere sound and when chief Maturahuatera settled on the shore there, the fish made his home in a sea cave at the base of the rocky inlet Kaimahi, on which a beacon now stands, just off Mataka Point which juts out into the sea between Paparoa and Tokaiti or Blowhole Point on the eastern shores of the peninsular that shelters the deep-water bight called Port Ligar, at the mouth of Pelorus. The mouth of the cave is visible at low water but completely covered by the tide. So here our taniwha lived, and from here he was wont to be summoned when required by means of incantations pronounced by Maturahautera and his descendants right down to the time the Europeans first came to these parts.

In ancient days, Kaikai-a-waro was revered by my people and when they went out to fish for hapuku and rock cod and their sea god appeared they were always careful to throw him some of their fish as an offering-food for their taniwha and pilot. And, Kaikai-a-waro was a guide to conduct toward their destination canoes passing between Holere mouth and TeAumuti and Whakatu. He use to proceed the canoes, leading them safely along the way they were to go. And he played around their bows just as he does today around the steamers and the launches of the pakeha.

Koangaumu, descendant of Matuahautere, lived 5 or 6 generations ago. To his assistance, when in dire need came his sacred taniwha-fish. It was in this way Koangaumu, in the course of fighting against the Ngati-Tumatakokiri people, was taken prisoner by them on Nuku-waiata and was shut up in a house by his enemies. He was to be either killed or enslaved.

One or two of his relatives shared his captivity and hastily built a little raft of dry flax stalks and, making rough paddles, set out upon the sea. In his dire need, Koangaumu repeated karakias to his gods and called upon his taniwha “Kaikai-a-waro” for aid. And the god-fish heard and, swimming across from his sea cave at Kaimahi, he found the distressed chief and his friends floating on their frail little raft. So Kaikai-a-waro took them in charge. He swam slowly along in front of the raft, flashing like fire in the darkness of the sea, and joyfully the fugitives paddled along after their pilot. He led them safely southward into smooth water, and they reached the shore of the mainland on the western side of Hikurangi. That was one of the benevolent deeds of my ancestral fish-god.

But there is another and more wonderful story of “Kaikai-a-waro.” It is the story of how the chieftainess Hinepoupou swam Cook straight, from Kapiti Island to Arapawa Island, in order to reach her home on Rangitoto, which is on the northern side of the French Pass. Hinepoupou was a cousin of Koangaumu, the chief of whom I have spoken. She was married to a chief named Maninipounamu, and their home was on Rangitoto. They went on a canoe expedition to Kapiti Island, 50 miles away across the Sea of Raukawa. Maninipounamu, being desirous of taking a new wife, deceitfully abandoned Hinepoupou at the south end of Kapiti and secretly set off with his men and sailed back to Rangitoto. When he returned to the island he was met by Hine’s mother, who asked him, “where is Hinepoupou?”

“Oh,” said the faithless husband, she met her death at Kapiti. She was killed there by the people of that island, and we had to fly for our lives.”

Meanwhile Hinepoupou, the deserted, sorrowed sore on the shore of Kapiti and pondered how to cross the dreaded Sea of Raukawa to her friends. She had no canoe, and she feared to venture to the northern end of the island, where she might be in danger from the alien tribe who delt there. At last, she resolved in her to swim the strait to Arapawa, 30 miles across. It was a swim far beyond human endurance, but could she not summon the sea god to her aid? First of all, she resorted to divination, after the ancient manner of the Maori, in order to discover what her fate would be. Going to a flax bush, she carefully plucked out the heart stalk at the root of the plant. If it broke short off it would have been a bad omen. But it did not break short off: it came out whole, and in a manner which indicated that her path lay safe and straight before her.

So, with confidence in her gods, the brave chieftainess took to the sea. She walked down to the extreme southern point of Kapiti Island and, gazing over the sea to the mountains of her island home, she recited an invocation to her gods for aid to cross the strait and for strength to sustain her in the ocean swim; and, having chanted her song, she cast herself into the sea and struck out for Arapawa Island.

And, her invocations she kept murmuring as she swam were answered. Her tribal taniwha, Kaikai-a-waro came to her aid. Yes, this very fish whom you call “Pelorus Jack” bore her up in her dire need. He heard her cry far across the sea and, leaving his ocean cave at Holere mouth, sped like a darted spear to the chieftainess’ succor.

Far out in the Sea of Raukawa he found her and, piloting her and bearing her up, he brought her in safely across the swelling seas and to Arapawa Island, and thence she went to Rangitoto, where she rejoined her people. And there is the story of her revenge upon her faithless husband, Maninipounamu, but I will tell that another time. This was one of the deeds performed by that kindly sea god of mine. This tale of Hinepoupou is no fiction. There are proofs of it.

On the cliffside oat the south end of Kaptiti you will see at this day two rocks called “Nga-Kuri-a-Hinepoupou.” They are the two dogs of Hinepoupou turned to stone. When she threw herself into the water to swim across the Sea of Raukawa, her dogs were afraid to follow her and remained howling on the shore, and so they were turned to stone.

And from that day to this “KaiKai-a-waro” has been the guardian of our people, the Ngati-Kuai, when they go out upon the sea. When white man’s religion was brought to this country the fish disappeared for a time. The Maori used to repeat chants to him, but the influence of the Christian missionaries was superior to the words of the Maori priests. Still the priests wished that he might return and be a pilot as before for the canoes of the Maori chiefs. And, in the course of after years, when fishing was carried on these waters, this fish reappeared.