A Mystical Ode to Peaches (and a Caution About Pits)

Bucket of peaches. Photo by Lauri deGaris.

Bucket of peaches. Photo by Lauri deGaris.By Lauri deGaris

Recently, I took a trip to Indian Springs, just north of Macon, Georgia. On my way home I decided to take Georgia County Road 142 from Jackson to Eatonton. When I got to Eatonton, I stopped at a roadside stand and purchased fresh Georgia peaches. I was thrilled to find a peck of ripe peaches for a reasonable price. And, in typical Lauri fashion, I pondered over the natural history of peaches as I devoured several on the drive home. After a few weeks of peachy research, this is what I discovered:

Peaches (Prunus persica) are native to China. They are believed to be first domesticated around 7,500 years ago. The delicious yet delicate flesh of a peach surrounds one of the hardest and hardiest seeds in the world. Dried peach pits travel well. The seeds are easy to germinate. And, peach trees fruit heavily. It is no wonder that peaches are found in so many gardens and groves around the globe.

In China and Japan, peaches symbolically unite humans with the divine. The tangled branches of the sacred peach tree reach to the sky, serving as a ladder for gods to move between heaven and earth. Peach wood is also honored, as it contains ling, a spiritual force that guards against evil spirits.

During the Yuan dynasty (1260-1368 C.E.), the Taoist gods gathered for a peach festival at the request of Xiwangmu, the Taoist Queen Mother from the West. After 3,000 years, the peaches of immortality were ripe and deserving of celebration.

Peaches reach North America in the mid-1500s. Spanish priests planted peaches in St. Augustine gardens around the mission site of Nombre de Dios. By the early 1600s, peaches were reported as far north as Jamestown, Virginia. And in 1700, naturalist John Lawson wrote that the land in South Carolina was “a wilderness of peach trees.”

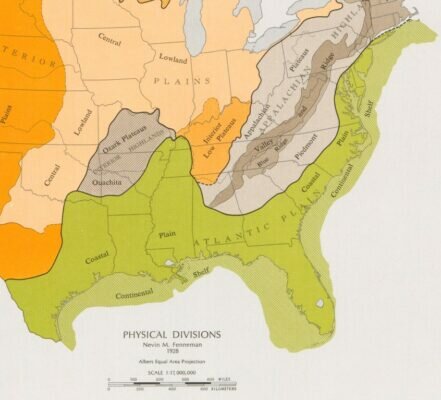

The most prosperous place for peach production follows the path of the fall line in the southeast United States. The fall line is the boundary between the geological features of the Piedmont and the Atlantic Coastal Plain. The fall line extends from Cape Cod to Mexico.

Fall Line Map. Photo courtesy of United States Geological Survey.

Fall Line Map. Photo courtesy of United States Geological Survey.The Atlantic Coastal Plain was ocean bottom as recently as 40 million years ago during the Oligocene epoch. The fall line was the shoreline of this ancient ocean. In Georgia, the fall line runs through Augusta to Macon and then on to Columbus. Along the fall line, soil from the Piedmont mixes with soil from the Atlantic Coastal Plain creating a distinct agricultural belt running along a long line.

Thomas Jefferson planted 1,157 peach trees in his north orchard at Monticello in 1794. The harvested fruits were turned into peach liqueurs and hog feed. Jefferson’s peach collection included 38 varieties propagated by Alexander Hepburn, personal nurseryman for the president.

Enslaved individuals provisioned their underground journey to freedom in untended peach orchards. Herbert Covey's “African American Slave Medicine” lists many medicinal uses for the peach tree. One of the most widely cited is a tea made from peach tree leaves that treats malaria, chills, and fever.

In 1879, peace in the Muscogee Creek Nation fell apart, and civil war ensued. The Green Peach War developed from grievances about constitutional forms of government. Battles were fought with much spiritual medicine and few casualties. According to several historical accounts, hungry soldiers helped themselves to green peaches in surrounding orchards. And, that is how the Green Peach War got its name.

During World War I, the State Commissioner of Horticulture reported in California the manufacture of oil from peach pits. The industry created a new use for peach pits, which were previously thrown away or used for fuel.

By June 1918, the United States government paid $7.50 per ton for dried peach pits to be used in the war effort. The war department also discovered that peach pits could be successfully used for munitions work. And, the outer hull is said to make charcoal six times as effective in absorbing poisonous gases on the battlefield as ordinary wood charcoal. The extraordinary qualities of peach charcoal make it possible for men to stay in “gassed” trenches for 18 hours while ordinary charcoal becomes saturated in three hours. The Indy Star reported that “200 peach stones will make enough carbon for a gas mask, and one gas mask will save an American soldier’s life.”

The secret processes of gas mask manufacture utilizing peach pit charcoal were carefully guarded. Numerous national news articles published in June 1918 reported that the peach pit output worldwide was cornered to prevent enemy manipulations.

By September 1918, the United States government called on all citizens to gather and dry the pits of peaches, apricots, plums, cherries and prunes, as well as hickory nuts, walnuts and butternuts. Special campaigns were designed to get the youngest Americans involved in the war effort. Stores, theaters, churches, and schools served as designated depositories for fruit pits. The Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts of America collected more peach pits than all other community efforts.

After World War I, festivals honoring the peach were planned and dramatized throughout the Georgia peach belt. Peach pageant themes revolved around a young maiden traveling the world searching for her eternal love. Finally, the maiden locates her love living in Fort Valley, Georgia, also known as Peach County, Georgia. This tale is the basis for Georgia branding itself the peach tree state.

Since the 1950s South Carolina and California consistently produce more peaches than Georgia. And, in the world market, China, Turkey, Spain, and Italy also assert their dominance in global peach production and exports over the state of Georgia. However, Georgia still claims to be the peachiest of them all.

For me, peaches evoke thoughts of abundance. And, I consider the appearance and taste of the peach as sacred. Recently I told my dear friend Mary Archer I was going to write about peaches. I asked her if she had any peachy thoughts to share on the subject, as I knew she grew up in the peach belt of Georgia. She immediately began to describe the alchemy that transpires as one bites into an almost over-ripe, juicy peach. She explained that an almost over-ripe juicy peach, one just on the verge of fermentation, becomes magical and mystical, certainly deserving of divine guardianship. I thought to myself this was peach poetry at its finest.

I also discovered that not all peach prose is full of promise. Emily Dickinson wrote a personal letter to Samuel Bowles and told him, “It was as delicious to see you as to eat a peach before the time it is ripe.” I believe Emily was less than impressed by Samuel’s company. She compares unripe peaches to stones, suggesting his company was not very loving.

Peaches are like edible poetry to me. And, after eating several almost overly-ripe, juicy peaches, I was primed to pen the following poem:

Welcome Summer Peaches

Ahhh, the beauty of a rose

And the sweetness of a peach

It is no wonder we love them both, so

They belong together -- they are family you know.

Late May, early June peaches first appear

July, named for Caesar, means the best is near.

Harsh summer sun is needed to ripen

Sweet southern peaches just for our liking.

Freestone and Clingstone are two varieties we grow

One clings to the center stone and the other lets go.

Ripe peaches, soft with fuzzy skin for protection

Once removed reveals succulent perfection.

Please give me

Peaches fresh from the tree.

Peach preserves,

I am quite sure,

I do deserve,

Peach salsa, peach cobbler, peach chutney too.

Here is a hint,

Serve over ice cream

Peaches with mint.

Welcome summer peaches

I await the pleasure

Of your peachy sweetness

I truly love and treasure.

--

One last note regarding peaches from the Poison Control Center:

Peach pits and other seeds from the plant family Prunus contain a potentially dangerous chemical called amygdalin that can create poisonous cyanide when digested. While swallowing a single pit is unlikely to cause cyanide poisoning, consumption of several unprocessed pits can produce symptoms.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here