By Anne H. Oman

Reporter-At-Large

December 14, 2017 7:38 a.m.

Dunes are formed by wind, waves and tides and held together by vegetation, which traps the sand grains.

How do we make sure that humans let the wind and waves and tides do their work and prevent hurricanes from drowning our island?

Frank Hopf, a local resident who earned a PhD in Geography and Geomorphology from Texas A&M, put that question to a packed house at the Amelia Island Museum of History last week. To find the answer – and to explain how the dunes and the island itself got here – he took the audience back in time hundreds of million years, to when Amelia Island was just a dot on the map of a mega-continent called Pangea, situated somewhere in West Africa near present-day Dakar, the capital of Senegal.

Fast forward another few million years and Pangea breaks apart and the Atlantic Ocean forms. Lo and behold, our little dot on the map is now part of North America. Then, but ever so slowly, the molten rock under the earth wells up and makes the mountains crumble, creating the gravel and sand of the coastal plain and the continental shelf.

By this time, some 130,000 years ago – in the Pleistocene era — “most things were in place for the establishment of a barrier island,” said Dr. Hopf.

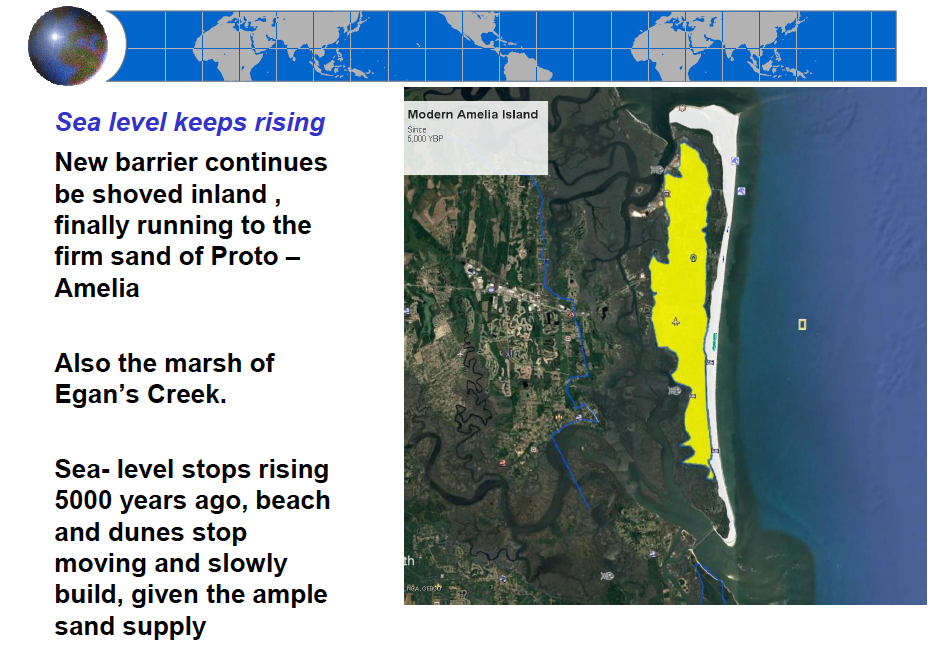

And so, the “proto-Amelia Island”—a long, sandy hill extending from about the present location of the lighthouse to where the Amelia Plantation shops are today — was born.

“If a sand oak grows there, it was probably part of the Pleistocene island,” he said.

Thousands of years later, the coast moved out and a new barrier island formed, which eventually — very eventually – attached itself to the old one.

Et voila, the place we now call home — the Amelia Island of broad beaches and marshes teeming with wildlife.

But can we keep it?

The answer may depend, to some degree, on how we treat the dunes.

“Dunes are critical to beach and barrier island stability,” said Dr. Hopf.

They also mitigate the effects of hurricanes. Hurricane Irma was not a disaster because “we had healthy enough dunes to prevent wash over.

Dr. Hopf calls the beach “a great energy dissipation system” that protects the land from the sea. Waves break when they hit the sea bottom in shallow water. They pick up sand and move it. Dunes store sand to help the beach survive storms and prevent sand from blowing inland. A key role is played by the vegetation — the sea oats, seaside pennywort, dune panic, beach cord grass, and other plants that hold the dunes together.

Dr. Hopf calls these plants “the goddesses” and warns they are not to be trifled with.

Dr. Hopf calls these plants “the goddesses” and warns they are not to be trifled with.

“They’re tough girls,” he said, “but they can’t handle being driven on, walked on, or camped on.”

All of these actions are prohibited under Florida law. Under state law, driving on dunes or destabilizing vegetation is a second- degree misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in prison.

“Do fences work to stabilize dunes?” asked an audience member.

“Vegetation works better,” said the scientist, “but fences can keep cars off.”

Dr. Hopf does not fault beach driving per se, but says that drivers need to steer clear of dunes.

Nassau County Sheriff’s Officer Jason Gray, who was patrolling the county’s Peter’s Point Beach Sunday, told the Observer that driving on the dunes gets the offender a $150 citation from the county. Camping on the dunes is also an offense that merits a $150 ticket, he said. Officer Gray said he normally informs campers of the law and gives them a chance to move before issuing a citation. Offending drivers and campers are told to leave the beach and not return that day.

In addition to the vegetation on the dunes, the wrack –the brownish mish-mash of kelp, sea grass and other debris that piles up just above the high-tide mark—is also worthy of respect, according to Dr. Hopf.

The wrack does triple duty on the beach. It provides food and shelter for shore birds and insects. It serves as an incubator for the vegetation that grows on the beach and helps anchor the dunes. And, the spongy wrack collects sand used to form additional dunes.

“People don’t appreciate wrack,” he said. “We need to educate people on the value of wrack.”

There are posters detailing the role of the wrack on display at the North End Beach Park, Main Beach, and Seaside Park.

After Hurricane Matthew, that lack of appreciation resulted in some clean-up contractors removing wrack from city beaches.

“That won’t happen again,” vowed Fernandina Beach Vice Mayor Len Kreger.

Mr. Kreger is the “go-to” person on the City Commission for the beach renourishment program that will be starting later this month. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will dredge the St. Mary’s river channel north of Fort Clinch and deposit some 740,000 cubic tons of sand compatible to the existing sand in grain size and color on the a 1.5-mile stretch beach from .5 miles north of Jasmine Street to Sadler Road. The work is expected to be completed by March 31 so it will not encroach on sea turtle nesting season.

Vice Mayor Kreger told the Fernandina Observer in a telephone interview that the Comprehensive Plan mandates that the city protect the dunes. He is currently drafting a Dune Master Plan, required under the Comprehensive Plan, which should be completed next month. The plan will identify any deficiencies with the walkovers and walk-throughs of the city’s 48 beach accesses. The city is currently replacing two walkovers — #35 South (Suwanee Access} and #40 (Pasco Access).

Of the 48 beach access points, 23 are structures, according to Fernandina Beach Parks and Recreation Director Nan Voit.

“In some places, the city’s right-of-way is too small to build a structure on,” she explained.

In the past, the Parks and Recreation Department worked with volunteer groups to plant dune-stabilizing vegetation, mainly on the north end. Now, said Ms. Voit, the vegetation is holding its own.

Trespassing on the dune “has typically not been an issue,” she added, “because we provide paths. And most people know there are sticker-y plants and cactuses in the dunes.”

Some people have cut through the dunes and made their own walk-throughs, which the city has filled in, according to Vice-Mayor Kreger.

Home-made walk-throughs allow water to surge through during storms.

Overall, how are we doing in the effort to preserve the dunes and prevent wash over during storms?

“I moved here because I found it to have the best protected natural beach/dune system on a developed beach community I had seen –not perfect and we need to continue to improve,” said geomorphologist Hopf.

So next time you go to the “great energy dissipation system”, use the designated access, keep off the sand dunes, respect the wrack, and please don’t pick the “goddesses.”

Editor’s Note: Anne H. Oman relocated to Fernandina Beach from Washington, D.C. Her articles have appeared in The Washington Post, The Washington Star, The Washington Times, Family Circle and other publications.

Editor’s Note: Anne H. Oman relocated to Fernandina Beach from Washington, D.C. Her articles have appeared in The Washington Post, The Washington Star, The Washington Times, Family Circle and other publications.

Great article. Thanks for the info. Fascinating. Good to have knowledgeable people looking out for our greatest assets.